Kandahar

When Nafas (Nelofer Pazira) receives a letter from her sister in Afghanistan saying she will commit suicide on the last eclipse of the twentieth century, she races from Canada in an attempt to save her. Nafas' journey will touch upon the multiple hardships faced by Afghanistani women in Iranian writer/director Mohsen Makhmalbaf's ("Gabbeh") "Kandahar."

Laura's Review: A

Along with the Iranian "The Circle," "Kandahar" make a strong indictment against a society's treatment of women without forgoing filmic artistry. Makhmalbaf's new film features some of the most haunting images of the year.

Nafas views the ruggedly beautiful, mountainous landscape from a helicopter before disembarking and donning the traditional burka, which covers her from head to toe. In addition to this disguise, she's forced to make an arrangement to travel with a family, it being illegal for a woman to travel alone.

Dolls are dropped in a town square and strangely left where they land. Only later will we learn that Nafas' sister lost her legs to a Russian bomb disguised as a young girl's plaything. Nafas' travelling family is robbed on the road, even though they possess practically nothing. She meets an American doctor, Khak (Sadou Teymouri), who we witness dispensing medical advice to a woman from behind a sheet. He drops his disguise, his beard and medical degree, to Nafas and explains that with only a rudimentary Western knowledge of medicine, he's offering these women far better care than they'd receive otherwise. Children can flip between recitations of their prayers and the use and care of automatic weapons. In a poverty stricken land, Nafas is offered the ring from a corpse because it matches her eyes. In the end, Nafas is spiritually imprisoned by the country she wished to free her sister from.

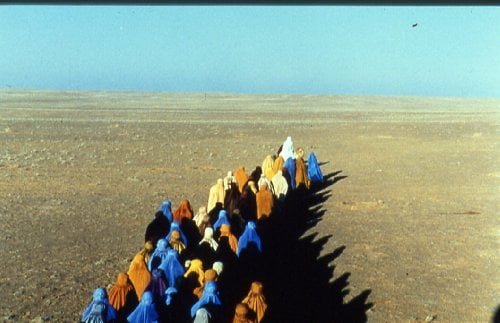

Makhmalbaf used a similar story which was told to him to fashion this dismaying yet poetic journey. His images are startling. Jewel colored burkas have never looked more beautiful and at the same time more horrifyingly nullifying. We see lips speaking through the slit of a burka made strangely foreign by Nafas' use of English. Approaching a Red Cross tent in the middle of the desert, a flock of black clad, one-legged men on crutches race toward an artificial leg dropping from the sky in a parachute. The beauty of the women can only be seen in their children, ironically made up with heavily kohled eyes.

Kandahar today is a changed destination than the one set out for by Nafas, but her journey in the cinematic "Kandahar" will forever be a statement for human rights.

Robin's Review: A

A young Afghani woman, Nafas (Nelofer Pazira), who immigrated to Canada, receives increasingly desperate letters about religious oppression from her sister still living in Afghanistan. When the latest letter states that she will commit suicide on the next solar eclipse, Nafas is determined to go to her sister's aid, but determination alone is not enough to overcome the cultural barriers she must face in Mohsen Makhmalbaf's "Kandahar."

Makhmalbaf's incredible tale of an Afghan woman's desperate journey to save her suicidal sister in the unapproachable title city may appear dated considering the events that have taken place in Afghanistan since September 11th. The recent fall of the oppressive Taliban regime in that ravaged country has given some hope to its people, but the writer-director's latest opus is far more universal and deals with religious tyranny and how a government can strip its people of their basic human rights in the name of "God."

"Kandahar" is an artistic road movie that follows Nafas, a female journalist who fled the country as a teenager, as she attempts the impossible: re-enter the country of her birth illegally, without suitable male escort, and stop her sister from committing suicide over the despair of living under the yoke of Islamic fundamentalist belief. The Taliban, who have shirked any Western enlightenment or technology to the detriment of the Afghan people, have forced strict adherence to the scriptures of the Koran on all, with women faring, by far, the worst. Among other restrictions the fundamentalist Muslim law requires that a woman wear the traditional burka, a head to toe garment that covers all, even the eyes, whenever in public. Nafas must wear the oppressive garment as a disguise that may help her reach her sister before the designated death day, only 72 hours hence.

Along the way Nafas meets and is helped by various characters to find her way to Kandahar. She is aided by an expatriated American who came to the Afghani-Iranian border as a fighter and became a "doctor" to the starving, damaged refugees - even his rudimentary medical experience is hands above anything else these people would ever see as he gives the needy food and medicine. Help is also provided by a one-armed con man who wheedled a set of artificial legs from a field hospital catering to landmine victims. Nafas even seeks the cover of a wedding party traveling to Kandahar to attain her goal in one of the film's many striking images.

The screenplay, by Makhmalbaf, is based on the real-life story of "Kandahar's" star, Pazira , who immigrated to Canada with her family in 1989 at the age of 16. For years she kept in contact with her close friend, Dyana, whose letters became more and more despondent over the treatment of women in their country. Pazira sought the help of Makhmalbaf to get into Afghanistan to save her friend, but nothing could be done, forcing Nelofer to return to Canada. Her plight spawned the director to create a fictional version of the young woman's journey, making Dyana's character the sister of Nafas, giving the tale a further sense of urgency.

Iranian filmmakers, for many years, have used striking images in telling their stories and veteran Makhmalbaf and his cinematographer Ebraham Ghafouri create some of the most indelible pictures of a world totally alien to us in the west. One sequence depicts scores of one-legged men frantically trying to get to the site of an airdrop where artificial legs fall from the sky. Another, when Nafas tries to infiltrate the wedding party, shows a throng of woman, covered by their vividly colored burkas, trekking across the harsh desert landscape in a stunning visual display.

The sheer artistry of the images of "Kandahar" is, alone, a reason to seek out this terrific film but there is more to it than just good looks. Nafas's vain attempt to save her sister's life is gut-wrenchingly vivid in showing the desperate hopelessness of her cause. The hard, dangerous life of the Afghans is punctuated with a look at a Red Cross station where two female doctors dole out artificial legs to the ever-growing population who are victims of the many land mines scattered and forgotten across the war-torn country. The picture of the dozens of one-legged men racing across the desert to lay claim to one of the fake limbs being dropped by the humanitarians is shocking, beautiful and extraordinarily emotional.

There are no professional actors in all of "Kandahar" and the use of Nelofer Pazira to tell Nafas's story proves effective. Her handsome face and startling gray-green eyes, though only briefly seen, help to give humanity to the burka-cloaked women whose hands are the only part of the female body allowed the light of day. The people she meets along the way are obviously not pros but this in itself provides freshness to the various characters Nafas meets on her quest.

It continues to astound me that the Iranian filmmakers are able to create such vividly artistic works on what is, by western standards, a pittance. Makers like Makhmalbaf are able to capture the eye, the mind and the heart with their simply told tales. "Kandahar" is one of the most poignant, powerful films of the year and continues the golden age of Iranian film.